The United States has ruled the global technology scene for decades, but China wants to rewrite that story. The world’s second-largest economy is pouring billions into artificial intelligence and robotics. At the heart of this effort lies a key ambition: to produce its own advanced chips that power these innovations.

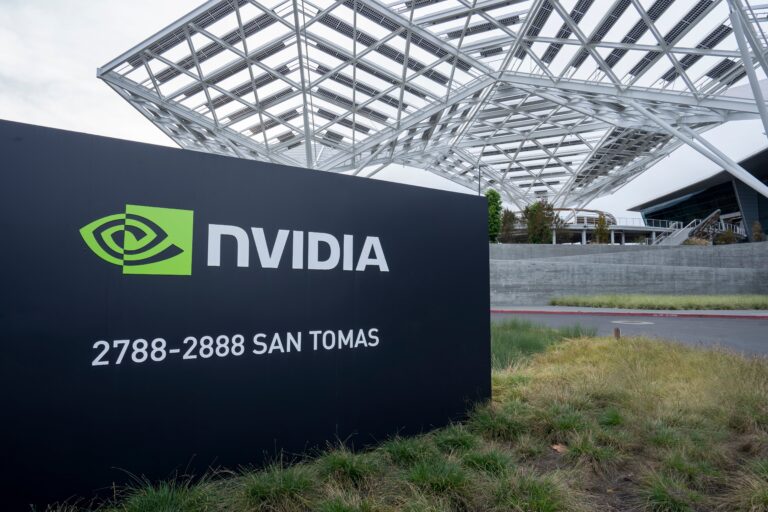

Last month, Jensen Huang, the head of the Silicon Valley chip powerhouse Nvidia, warned that China was just “nanoseconds behind” the United States in chip development. Can Beijing match American technology and end its dependence on imported high-end chips?

After DeepSeek: China’s Confidence Surges

China’s DeepSeek startled the tech world in 2024 when it unveiled a rival to OpenAI’s ChatGPT. The announcement from this relatively unknown startup was remarkable because it claimed to train its model at a fraction of the usual cost. The company also said it used far fewer top-end chips than other AI firms.

The launch temporarily shook Nvidia’s market value and marked a turning point for China’s ambitions. Since then, momentum in the Chinese tech sector has only accelerated. Major firms now declare openly that they want to rival Nvidia and supply their own high-end chips to domestic companies.

In September, Chinese state media announced that Alibaba had developed a new chip matching the performance of Nvidia’s H20 semiconductors while consuming less energy. These H20 chips are versions modified for China under U.S. export rules.

Huawei also presented what it described as its most powerful chips yet, along with a three-year plan to challenge Nvidia’s leadership in AI. The firm promised to share its designs and software with Chinese developers to reduce reliance on American products.

Other companies have followed suit. MetaX has secured major contracts with national giants such as China Unicom. Meanwhile, Beijing-based Cambricon Technologies has become another rising star. Its shares in Shanghai have more than doubled in three months as investors bet on China’s homegrown chip drive.

Tencent, the company behind WeChat, has also embraced the government’s call to use Chinese chips. Across the country, trade shows promote these firms to attract investors and highlight Beijing’s growing confidence.

A spokesperson for Nvidia said that competition had truly arrived and emphasized that customers would pick the best technology for their applications. The company added that it would keep working to earn developers’ trust worldwide.

Still, some experts urge caution. They note that many Chinese claims lack public data and consistent testing. According to computer scientist Jawad Haj-Yahya, who has tested both U.S. and Chinese semiconductors, Chinese chips perform well in predictive AI but fall short in complex analytics. “The gap is shrinking,” he said, “but catching up in the short term remains unlikely.”

Where China Leads — and Where It Still Lags

On a recent technology and business podcast, Jensen Huang praised China’s vast talent pool, intense competition, and rapid chipmaking progress. He called it a “vibrant, high-tech, modern industry” and warned that the U.S. must compete “for its survival.”

That assessment likely pleased Beijing, which has long sought to become a global tech leader and reduce dependence on Western suppliers. For years, China has poured billions into what President Xi Jinping calls “high-quality development,” spanning renewable energy to AI.

Even before Donald Trump’s return to the White House, Beijing had spent vast sums transforming its economy from a manufacturing base into a hub for cutting-edge industries. The renewed tariffs war with Washington has only intensified this mission. Xi has vowed to make China more self-reliant and less dependent on “anyone’s gifts.”

Huang also warned that the U.S. should keep trade with China open or risk losing ground in the AI race. That warning came just as Beijing launched an anti-monopoly investigation into Nvidia.

However, China’s state-led model can sometimes hinder innovation. Professor Chia-Lin Yang from National Taiwan University argues that focusing too much on shared goals can stifle disruptive ideas.

She added that Chinese chips still face criticism for being less user-friendly than Western products. Yet, she believes the country’s massive pool of skilled engineers can soon close that gap. “You cannot underestimate China’s ability to catch up,” she said.

Chips as a Bargaining Tool in the U.S.-China Rivalry

Professor Yang described China’s new chip announcements as a “bargaining chip” in its ongoing tariff talks with the U.S. Beijing wants to pressure Washington into resuming sales of advanced equipment or risk losing access to the Chinese market, said Dr. Haj-Yahya.

These announcements project strength even as China likely still seeks American technology. Most experts agree that China remains reliant on the U.S. for the most powerful chips, at least for now. Semiconductor engineer Raghavendra Anjanappa said Beijing still needs some American components for advanced projects to stay competitive.

He noted that China can replace U.S. chips in less complex systems but lacks the raw performance required for high-level AI training. Despite recent breakthroughs, China still trails in supply chain maturity compared to the U.S., South Korea, and Taiwan.

Meanwhile, Washington has tightened export restrictions to slow China’s progress. The U.S. recently blocked access to Nvidia’s top-tier chips, striking directly at China’s weak point. “The U.S. has hit China exactly where its dependency runs deepest,” said Raghavendra.

“But China isn’t far behind,” he added. “They may only need five more years to achieve full independence.”